Mixing coal and solar energy India’s route to sustained economic growth

Sudheendra Kulkarni has been no stranger to controversy on his journey from socialist to advising leaders of the conservative Hindu nationalist party that runs the country now under pro-business Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

And in October 2015 his iconoclastic status was underlined when he was doused in black ink by extreme right-wing activists because he was taking part in the launch of a book by a former foreign minister of Pakistan. “I realised very late in my life that Marxist ideology is not suitable in India. In fact, I would say it is unsuitable for any corner in the world,” he said after the attack, explaining his diverse political views.

So it is perhaps not surprising that after an interview about diplomatic issues he pauses to quietly say he wants to talk about climate change and it “might not be what you will hear from other people”.

Kulkarni, who now heads the Observer Research Foundation Mumbai think tank funded by the Reliance business group, says: “India and China should be bold enough to see that even though they may have lower per capita carbon emissions they should take responsibility for cutting emissions. It’s a common problem. We have to reconfigure our economy.”

This is one of the biggest conundrums surrounding the economic renaissance promised by the Modi government. It is equally proud of having boosted Indian domestic coal production to record levels in the past year, while at the same time setting out on what could be the fastest increase in renewable energy in the world.

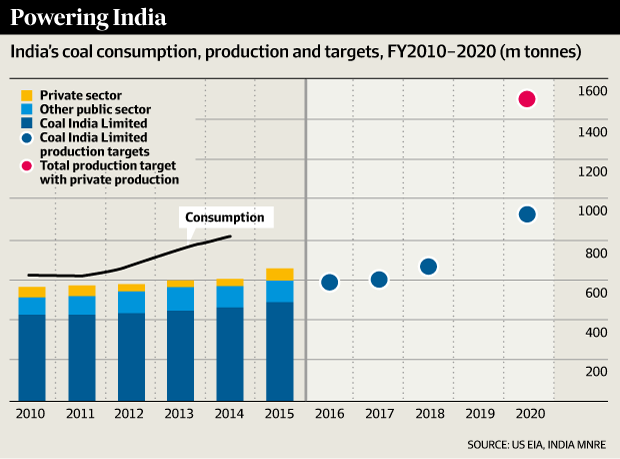

Double Coal Production

State-owned miner Coal India aims to more than double its coal production from about 600 million tonnes a year towards 1.5 billion tonnes by 2020, after a shake-up by the government that has speeded up auctioning of licences to private miners and eased environmental constraints. In an indication how this is hitting foreign suppliers, government officials have talked of imports falling to about 170 million tonnes this financial year, from about 220 million tonnes in the previous year.

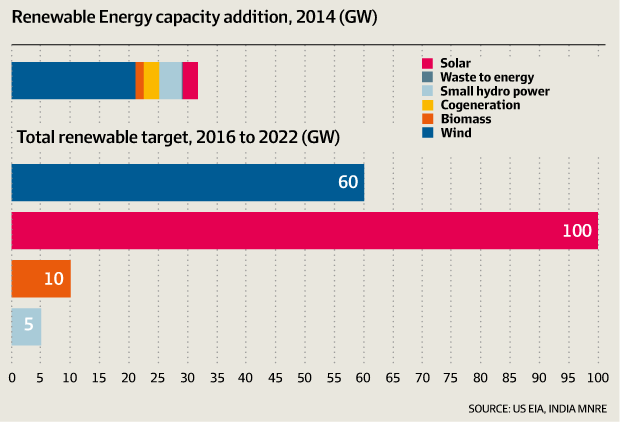

The government is also committed to producing 175 gigawatts of renewable energy by 2022, including 100GW of solar. This compares with total power generation capacity today of 280GW, which includes about 60GW of renewable energy and 4GW of solar. Forecasters say the country needs to build about 15GW a year of new capacity to meet demand.

These contrasting policy objectives are producing starkly different projections from analysts for what longer-term demand for imported coal from countries like Australia will be. In February industry consultant CRU Group issued a report forecasting that Indian coal imports would start increasing after 2020, as mining and infrastructure constraints retard its domestic production ambitions.

It said domestic output would expand to 810 million tonnes by the end of the decade, less than the targeted 1.5 billion tonnes, which would open the possibility for an increase in shipments to what is now the world’s second-biggest coal importer.

But at the same time, the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis has seized on the recent import declines of about 30 per cent a month from the same time a year ago as evidence of waning long-term need for imports. These declines compare with annual import growth of 20-30 per cent in the past five years, which made coal Australia’s biggest export to India, valued at $5 billion to $6 billion a year. But the institute says there will be little need for imported coal by about 2021.

In a report in 2015 the Australian Department of Energy questioned India’s ability to meet its coal-production target, saying: “Growth in production is likely to be constrained by difficulties in accessing land, lengthy approval processes, inadequate transportation systems and poor productivity, largely stemming from the use of outdated production techniques.”

India has about 100GW in new coal-fired power approved or under construction, which is about half the existing coal power and similar to the planned new solar capacity over six years. But after 2017 these are supposed to be modern, high-efficiency plants that run best on the high-energy, low-ash coal that Australia has but India lacks. The department says: “The roll-out of advanced coal-generation technologies in India presents a significant long-term opportunity for coal producers.

The International Energy Agency has forecast that while more than half of the new power capacity in India to 2040 will come from renewables and nuclear, India will still account for more than half the of the new coal power plants in the world over that same time. The IEA has also questioned India’s ability to produce 100GW or solar by 2022 because of finance, land and panel production capacity limits. It says a target of 40GW is more likely. This would probably support short-term demand for coal.

Energy Minister Piyush Goyal sought to resolve these tensions during his visit to Australia in February by saying while he was aiming for coal self sufficiency there would still be a need for Australian imports to feed new-generation power stations and to fill existing rail infrastructure gaps between Indian power plants and coal mines.

“Where it’s near-impossible to move coal over vast distances of the rail infrastructure currently will continue to be served by high-quality, low-cost Australian coal,” he said. “I think it’s a win-win situation for both countries how we can coexist as we dramatically increase [coal] production in India.”

Country of Surpluses

Goyal, a key figure in the Modi government often tipped for promotion, says increased coal production has “turned India from a country of shortages, as we were well known for decades, into a country of surpluses, with a great degree of enthusiasm among the people because we have kept all the prices affordable.”

But the minister also drew parallels between his task of rapidly boosting renewable energy with the way solar power was one of the highlights of Modi’s time as a state chief minister before he become the Prime Minister. He says the national renewable energy program is “an article of faith” for Modi. “I can assure you my renewable energy plan its going to scale up . . . and that’s one area in which my government is completely committed.”

While Goyal sees a role for Australia as a swing supplier of coal to fill the holes in India’s infrastructure and new power plants, he is focused now on encouraging Australia to cut the cost of its natural gas production to find a new market in India and to see the country as a place to commercialise solar technology at scale.

“Given the large quantities of gas that Australia is planning to produce, you will need large volumes of gas to be exported and India will be a big market. But we will only be able to give assured contracts if the pricing is also nearly fixed, so that the affordability of power can be ensured,” he says.

And combining Australian solar innovation and technology with Indian well-trained manpower and leveraging on the low-cost manufacturing base that Indian has to offer will allow Australian companies to market their products to a global audience, he says.

Access Concession Capital

Goyal still concedes that one of the keys to his renewable ambitions will be whether India can access concession capital from foreign development agencies, which he sees as an offset for the way India is being asked to rein in carbon emissions before it is industrialised.

This could be the flaw in the plan to reduce dependence on coal. However, with conservative commentators such as Kulkarni arguing that the emerging Indian middle-class demand for a cleaner environment has been underlined by community support for recent car-use limits in Delhi, the government might be raising expectations it will need to meet.

“I don’t think it is an insurmountable issue. What is needed to make climate change an issue is to give it a place in electoral politics,” Kulkarni says. “We should not make the mistake that others have made. We have to reduce our dependence on the fossil fuel that we import.”

LinkedIn Group about Renewables and Mining

If you are interesting about these topics, please you are welcome to participate on the LinkedIn group about «Renewable Energy for Mining and Oil Industry».